On accessibility and infrastructure

It seems to me that when decision-makers want to build infrastructure for transportation in urban areas, the discussion gets very heated. Land is scarce – so users, all of a sudden, become spokespeople for each mode which they most often use, fighting that enough land is provided to their mode.

In many ways this politicisation and discussion can be very positive because we appreciate the different perspectives when it comes to evaluating building long-lasting infrastructure. For this appreciation to be the case, different users and eventually their elected representatives must be able to understand and empathise with different needs of different modes.

But maybe we need to also see that we shouldn’t be fighting for land, we should be fighting for more access to land.

In the last 120 years, the cars have enabled normal people great things and increased the opportunities they have, in other words, a motorised vehicle has increased the accessibility of pretty much everyone. Metaphorically speaking, the world has become smaller right in front of us.

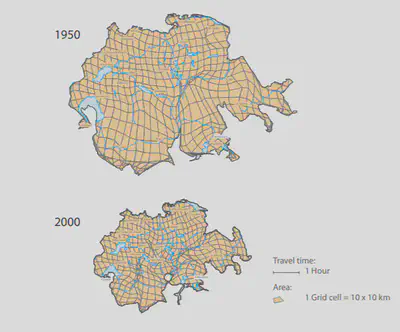

On the image below a map of Switzerland is shown. The cells are distorted dependent on the travel time across the cells. A travel time of one hour stays constant, so a smaller map, means faster travel. The maps between 1950 and 2000 are compared (Axhausen, 2008).

Accessibility is a term often used in transport and land-use planning, and is generally understood to mean approximately ’ease of reaching’. Accessibility is concerned with the opportunity that on individual or type of person at a given location possesses to take part in a particular activity or set of activities.

At the same time, this has also provided the opportunity to move further away from the city, which provides lower cost of housing and commute to work. However, as more people can afford to do this, and population further grows, this leads to traffic congestions on the highways causing slower traffic, increased delays etc.

As central business districts (CBDs) get less accessible, the companies generally react by moving jobs elsewhere, ceteris parabus. There are many reasons why companies decide their locaton and prefer to cluster with other firms, but the accessibility to a staff pool is an important one.

Back to the user: After the arrival of the automobile, there was clearly a leap for lower costs and improved accessibility based on the car infrastructure. As we see congested roads and revitalised cities, it is observed that this did not pay off for those families who invested in housing in the sub-urbs and travel long distances with car to their job. The accessibility to jobs is less in these cities. So what is the solution?

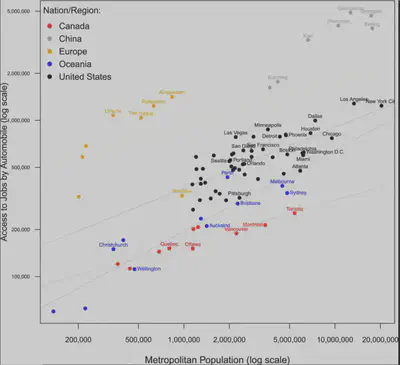

A recent Open Access paper published in Nature’s Urban Sustainability by Wu & colleagues approached infrastructure networks from a very interesting point of view. They looked at the accessibility to jobs in different cities calculated for different modes.

Two things I’d like to highlight:

What is less surprising, is that Dutch cities, famous for their cycling infrastructure, and other European cities such as Vienna, Krakow and Paris are among those cities with the highest accessibility to jobs by bike and by walking.

Second: A very interesting result in this paper, is that the Dutch cities also score very highly for the accessibility to jobs by car and score higher than other cities, which have focused less on “slow-mode” infrastructure. A lot of the heated debate on cycling infrastructure investment mentioned above, however, bases on the “fact” that more cycling infrastructure takes space away from cars, which can only be bad. Right?

This paper shows evidence that more cycling accessibility (provided by increased infrastructure and policy) correlates with more accessibility overall meaning that they complement each other very well. My hypothesis is that this happens because both people and their jobs stay in the “centers” of cities when people are provided with mobility opportunities, be it by car, bicycle or transit. This also makes it more interesting as a company to stay in CBDs as the staff pool is retained in those areas.

Therefore, we do not improve peoples’ opportunities by maximising efficiency of one mode – but rather providing choices for mobility.